The 17 Things That Changed Beer in the Past Two Decades

This blog started as a side-project on February 26th, 2006. I had been writing off and on about beer for various print publications for eight years at that time, but for the five or so previous years, only infrequently. Against all odds, it has somehow grown to consume a substantial piece of my work life, and I’ll be celebrating it in ways I hope are entertaining and not overly self-indulgent in the next week or two. Today we consider the major developments that permanently changed the industry.

I have observed a great many phenomena over the past 20 years. Most were fleeting trends that left no mark on an industry—glitter beer, Lemondrop hops, vortex bottles. But some developments were absolutely transformational; they changed the beer we drink, the way it was made, the ingredients breweries use, who is making the beer, and the ways it was sold, presented, or talked about. The funny thing is, we may not have noticed them at the time; even if we did, our brains normalize things so efficiently, we may not realize how amazing they would have seemed to our 2006 selves (those old enough to have been thinking about beer then).

In the first celebratory post of my 20 years blogging, I offer a list of the 17 most transformational developments in beer in the past two decades. I’ve let my crack “Book of Lists” research team sit this one out—this is one blogger’s ranking, based on very close study, of the those developments. It is the definitive list, confirmed indisputably by the voices in my head. If you dare disagree . . . that would be typical, actually. Over those twenty years, I’ve learned that hive mind is collectively much smarter than I am. So take these as an appetizer for discussion and let’s have a full meal discussing the topic.

17. Decline of Caramel Malt

From the late 1970s through the time I completed the manuscript for the Beer Bible in 2013, one of the most important markers of American craft beer was the use of caramel or crystal malt. It thickened ales (and even some lagers), sweetened them, and gave them a golden to amber hue. It had a huge effect on beer, and is in part responsible for the IBU wars of the aughts (the sweetness required balance). Even as I wrote about it in 2013, however, the decline was beginning as breweries shifted toward hop flavor and aroma, which turned treacly with too much caramel. Now most of the industry is allergic to this malt—to the point that many brewers eschew it even in styles where it adds a wonderful fullness and sweetness.

How I covered it on the blog: “The Slow, Steady Decline of Caramel Malt”

16. Large Brewery Consolidation

In 2006, the U.S. brewing industry seemed highly consolidated, with just three giants left and most of the regional domestic players dropping like flies. But that was nothing. Since then, Anheuser-Busch was gobbled up and Miller and Coors merged. This same process happened internationally, as large beer companies tried to forestall decline through mergers and acquisitions. All of the big three are now part of multinational conglomerates, and the largest U.S.-owned brewery is Yuengling. (Pabst is larger, but isn’t a brewery so much as a marketing concept.) Sierra Nevada is second if you exclude Boston Beer’s non-beer production, which you absolutely should. A consequence of this brewery consolidation is an even faster consolidation of distributors, notably the growing might of Reyes. It’s not interesting to craft beer fans, but it’s important, because the health of the overall industry, and especially domestic producers, sets the playing field for small breweries.

How I covered it on the blog: InBev Acquires A-B, “Big Beer Gets Bigger: AB InBev Buying Out Modelo”

15. Hop Products

This development will end up being far more significant in the long run than some of the items higher up the list, but it’s just getting started. As hoppy beers become the overwhelming favorite within the craft segment, huge innovation is underway—though it’s not happening on the style-development front. It’s in the way breweries piece together flavors and aromas using old-fashioned hops alongside a dazzling range of oils, extracts, concentrates, isolates , and—honestly, I can’t keep up. You don’t see these products listed on labels because drinkers don’t even care what kind of hops go into the beer now (perhaps because there are too many). But they are in the process of transforming the way brewers brew, and are only getting started.

How I covered it on the blog: “Hop Products Haven’t Displaced Hops. Yet.”

14. Smart phones

For centuries, technologies have exerted powerful, if unnoticed, effects on brewing and beer drinking. Cell phones are a perfect example. Twenty years ago, people didn’t have a computer in their pocket. They couldn’t immediately search on the best or closest breweries, or have a computer voice give them turn-by-turn directions to guide them there. People didn’t sit at bars staring into a glowing screen. They played more bar games. Nobody rated the beer and breweries online—they turned to “experts” for advice. Breweries had to advertise in physical newspapers. Now breweries and their customers communicate via social media. People consult a beer’s rating rather than the opinion of a mandarin like Michael Jackson. Slowly and almost invisibly, cell phones have reshaped the way breweries and their customers interact at almost every level.

How I covered it on the blog: All the ways phones have changed drinking.

13. The Fall of 22-ounce Bombers

Small breweries up until the late aughts had a perfect hack for their business model: the 22-ounce bottle. To begin with, it commanded a premium price; at $4-5 a bottle in the late aughts, it fetched around double the price of a six-pack, off-setting mobile packaging costs. As the new-brewery explosion happened around that time, it gave breweries an inexpensive way to put their products in front of potential new customers for sampling—and remarkably, the customers were happy to pay a premium for the chance to try a new brewery’s beer. Grocers and beer stores devoted tons of space to 22s. A number of breweries in that period used 22s to bulk up to medium-sized breweries, when they could afford to buy packaging lines and invest in distribution. It was great while it lasted.

How I covered it on the blog: “Trend Alert: Deschutes Scraps the Bomber,” “Stop Waxing Your Bottles”

Courtesy: Pacifico

12. Mexican Beer

At the turn of the century, imported beer was a marginal segment. That started to change in the aughts and it really picked up steam after 2010. Most of that growth went to Mexican breweries, starting with Corona. Though it was a long time coming, I think it would have been basically inconceivable to our 2006 selves that a Mexican beer would become America’s best-seller. Modelo may or may not be a stable number one, but never mind—the success of imported beer is one of the main ways we can measure the slow decline of domestic lagers. Mexican beers have been one of the most consistent growth areas in the beer industry, and they’re still the healthiest.

How I covered it on the blog: “Where Do the Imports Come From?,” Imports Mean Mexican Beer

11. Social media And The Death of Print

In 2006, if a brewery wanted to reach customers, it used traditional media. Ads in print publications, radio, and television. Big breweries might sponsor a sports team or buy billboard space. Those ads helped support a media network from the mid-20th century that was still basically in place. Blogs like this one were the “disruptors” of the early aughts, but they were nothing compared to what Mark Zuckerberg had in mind. By 2010, social media was providing breweries a new way to reach customers directly. Breweries’ ad dollars quit going to traditional media, which withered under the influence of the waves of social media rom Facebook to TikTok. Thanks to algorithms that no longer benefit small business, this may have been a net negative for everyone—except, perhaps, paid influencers. But either way, it was a big deal.

How I covered it on the blog: “Communicating Beer and Social Media,” “Are We Post-Social Media Yet?”

10. Rating Sites

In some ways, this may be the quaintest item on the list. The first gen sites, Beer Advocate and RateBeer, were really beta version social media for beer obsessives. They were really important in building connective tissue among the superfans who would champion craft beer. (A lot of people in the pre-Untappd days made real and lasting connections there, too.) Untappd, of course, was critical in the heat wave of the mid-teens that launched hazies, pastry stouts, smoothie sours, and all the rest. Especially given the overall sense of yuck that we now associate with ratings and social media, it seems a bit dreamlike to recall what a big deal these sites were.

How I covered it on the blog: “A Survey of Beer Apps,” “Trust Your Judgment”

9. Glassware

Back in 2006, the vast majority of beer in the U.S. was sold in shaker “pint” glasses that were, filled all the way to the brim, 16 or 14 ounces max. Selling beer in these “pint glasses” wasn’t necessarily a scam because it was so ubiquitous, but it was suss as hell. One of the great initiates of mine on this blog is the long-forgotten Honest Pint Project, which attempted to rectify this. I don’t flatter myself that it moved the needle much, but as the industry grew up, it started to recognize that people should know how much beer they’re paying for, with a now-expansive range of glassware to suit preferences as well as beer styles. Shaker pints aren’t dead, but they’re now pretty rare in beery places (and in the Pacific NW, they’re just rare period). This is one of the triumphs for transparency and consumer rights.

How I covered it on the blog: Cheater Pints, The IPA Glass

8. Buyouts

In 2006, all of the big three breweries were still independent, and only two craft breweries—in the entire country!—had sold even a minority of their shares to the bigs. That changed in 2011, when AB InBev made the Goose Island the first full-scale purchase of a craft brewery. It took a few years for other big breweries to follow suit, but soon the race was on. Notable hallmarks of the era included the billion-dollar buy-out of Ballast Point, the creation of Golden Road purely as a property to be marketed to AB (it worked), and the scrap-metal market that those previous purchases would become a few years later. Fast forward to 2026, and this is all old hat. Relatively few of the largest craft brands are independent. The shockwaves have mostly subsided, but they were huge at the time. We entered the 2010s with a childlike naïveté about the notion of independence, which meant that these sales brought the sting of betrayal—young drinkers would be shocked by the furor the sale of an Elysian or Lagunitas. By the time Covid hit, we had grown up and understood that it was always a beer industry, not a movement. We are naive no more.

How I covered it on the blog: “The Goose Island Deal,” “A Series of Fateful Decisions,” “Betting a Billion Dollars Against a Bubble,” “Tiny Chicago Brewery Purchases Brand Formerly Valued at $1 Billion”

7. Craft’s Ubiquity

When craft beer’s volumes plateaued, people began to minimize the impact craft beer had on the larger brewing industry. But this conceals the huge cultural change craft brought. Twenty years ago, people still looked at you funny if you asked for an IPA. Classy restaurants still served Heineken, not a local brewery’s beer, and good luck finding craft in an airport hotel bar, a dive bar, or a stadium. That has completely flipped. Now people reference IPAs on sitcoms, and you can get an IPA almost everywhere. Partly this is a function of the Pareto Principle, that 20% of the people consume 80% of the beer. It’s actually more exaggerated that that—10% of the people drink most of the beer, and they mostly drink mass market lagers. But that means the large majority of beer drinkers (80% +) don’t drink that often, and a lot of them drink craft. Twenty years ago, very few drinkers drank craft. Today most drinkers do.

How I covered it on the blog: Dive Bar Challenge, the drinker/volume distinction, “The Wallpaper Phase of Craft Beer”

6. Taprooms

For the first twenty years in the craft era, people drank beer in brewpubs, bars, or at home, and brewery business models were built around these retail opportunities. In the aughts, taprooms emerged as a real force. They were usually stripped-down places to buy a brewery’s beer, with little or no food, and uncomfortable chairs arranged around old barrels. They were cheap to build out, didn’t require breweries to open a kitchen—that’s a completely different business—and the hordes came flooding in. Covid seems to have permanently dented their prospects, at least in that stripped-down version, but from the mid-teens til Covid, they helped create a venue for all the new breweries opening up.

How I covered it on the blog: “The Return of the Tied House”

5. Bottles → cans

In our growing category of “things we wouldn’t have believed in 2006,” we add the nearly wholesale shift from bottles to cans, especially within craft brewing. This is partly a business story, but again, the larger part is cultural. In the 1980s, breweries (of all sizes) signaled their “premium” status by bottling their beer. Cans were considered cheap and disposable—not much classier than plastic. That relationship fractured in the mid-teens as hypey new breweries began releasing one-off batches of beer in 16-ounce cans—often with eye-watering prices. I suspect we’ll eventually see a move back to bottles to signal luxury, but for a lot of economic and environmental reasons, I doubt we’ll ever go back to a bottle standard.

How I covered it on the blog: “Cans Are Ugly” (2010), “The New Signal Cans Send” (2017), “Switching from Bottles to Cans: A Case Study” (2022)

4. Diversity

That the word “diversity” should come to be seen as controversial is a secondary artifact of the past twenty years in American society. But in terms of beer, it has been 100% positive. In 2006, brewing was one of the most male-dominated fields in America. It was extremely rare to find a single woman in the brewhouse. Then, in 2007, veteran brewer Teri Fahrendorf founded the Pink Boots Society. In the two decades since, it’s now less common to find a brewhouse that doesn’t employ a woman brewer. It has been slower going for people of color to found breweries or enter the industry, in part because as they were beginning to make progress, Covid hit, followed by a nationwide brewery slump. But projects like the Michael James Jackson Foundation and the National Black Brewers Association have helped more people of color enter the profession. For an industry struggling to find drinkers, reaching out to the 40% of non-white Americans and fifty percent of women makes basic financial sense. But in terms of inviting people who look like the country into the metaphoric pub, it makes a deeper kind of sense.

How I covered it on the blog: Diverse Breweries Database, “Teri Fahrendorf and the Pink Boots Society,” “Giving BIPOC Brewers an Equal Shot,” “Incubating More Than a Brewery”

3. COVID

At some point two or three decades from now, I think historians and sociologists will have a better sense of the scope of Covid’s impact—and it will dwarf events like the 2008 recession and the Iraq War. Probably, just as happened a century before with the previous great global pandemic, regular people will prefer not to remember. Yet the lasting effect has been profound on business models and the way beer is made, sold, and consumed. Of course, it went beyond that, in ways that also affected breweries. It reshaped cities and gutted downtowns, for examples, hurting the prospects of breweries located there. It hastened the shift to cans in the beer industry. It stopped the proliferation of satellite taprooms. The effects rippled through every part of society, and the social beverage of beer was caught very much in the middle of that.

How I covered it on the blog: The Coronavirus Diaries

2. Citra and hop breeding

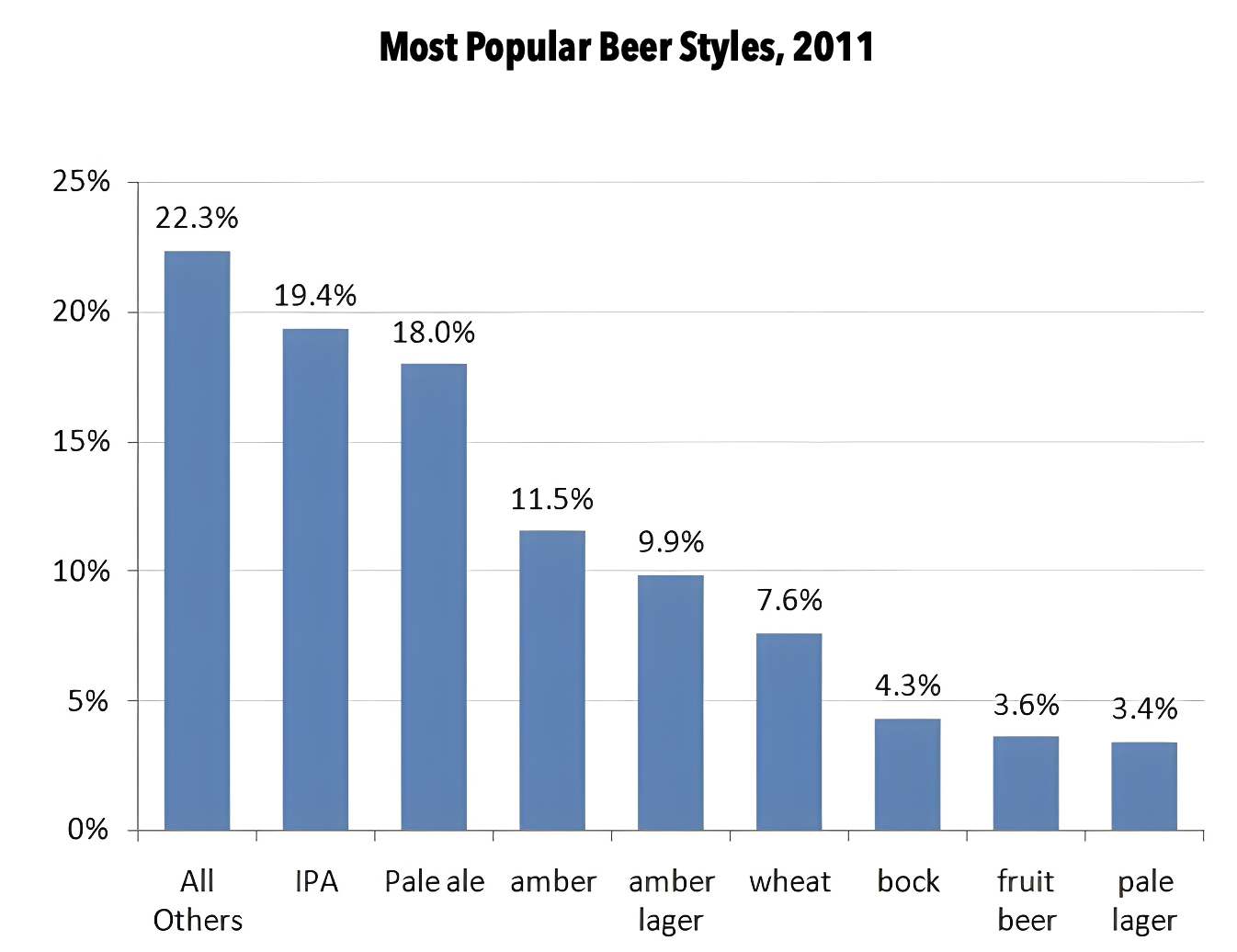

The final two items are a joined pair, and they are historic from a global beer perspective. From the first few breweries founded int the late 1970s through 2010, craft was a small segment of the beer industry dominated by mild styles of beer like wheat ales, pales ales, and amber lagers. IPAs were already rocking by the aughts in the Pacific Northwest, but that was a regional preference. Then the Hop Breeding Company released a new cultivar it called “Citra” and the course of craft brewing went toward hops in every corner of the country. Citra was the first of the modern type of American hop that was rich in fruit scents and flavors, and brewers immediately responded by making beer to take advantage of these qualities. Citra and the new-wave American hops allowed for a new kind of ale built around intense aromatics and flavor rather than bitterness, which appealed to a broad audience (see entry number 7). By 2011, the most popular craft style was IPA, and it would continue to grow every year after.

How I covered it on the blog: “The Citra/Mosaic Connection,” “Your Favorite Hops"

1. IPAs

Round about 2013, one of the common questions asked in articles and on message boards was “What’s the next IPA?” That is, what style would enjoy meteoric rise the way IPAs had over the previous decade? In 2012, I answered the question this way: “Time to quit thinking like that. The next great thing will be an IPA. And the great thing after that.” Indeed, what we saw in the 2010s was the emergence of an intact national tradition with American hops and various techniques to extract their fruity goodness at its center. We saw hazies come along and milkshake IPAs and Brut IPAs and cold IPAs and triple IPA in stovepipe cans and nouveau West Coast IPA. These were all variations on a theme. The American national tradition had been born, and though it would shift and evolve, it wouldn’t fundamentally change. It was such a striking development that it went international, and even now, as the beer market and the craft segment struggle, the bright spots are hoppy and aromatic. We haven’t seen the birth of a new national tradition since the 1840s, and this is easily the biggest story in beer.

How I covered it on the blog: IPAs become America’s most popular craft style (2011), “How ‘India’ Came to Mean ‘American’”

This list isn’t exhaustive. I considered other items as well: seltzer, which was the first hit beer took that dented growth (a category that includes canned cocktails RTDs and all the rest); AI, though it will probably have a more limited effect on the beer industry, which produces a tangible good; or the consolidation of distribution—though I mentioned it in the context of other points. What else did I miss? I’m back from Czechia and I can monitor the comment threads closely, so I’m turning them back on. Please do that bloggy thing and add your comments below.