Portland Brewing Company, 1986-2021

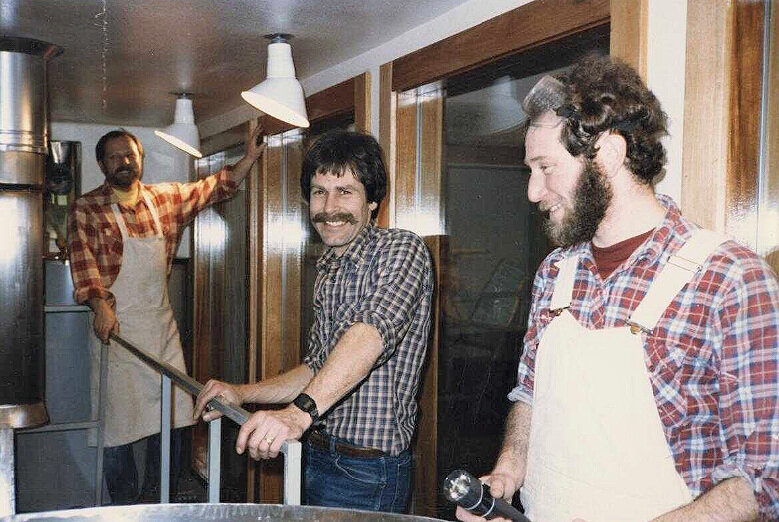

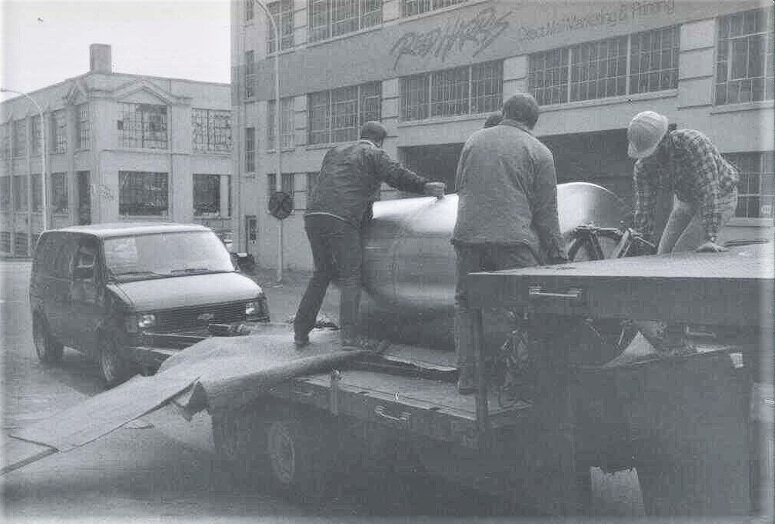

First brew, with (L-R) Frank Commanday, Art Larrance, Fred Bowman, and Bert Grant. Source for archival photos: Oregon Hops and Brewing Archive

Listen to this article:

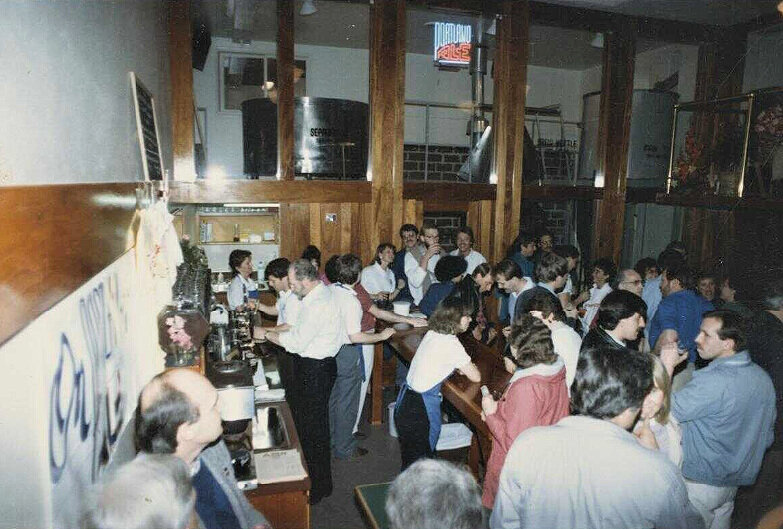

On the Friday afternoon of January 8th, Portland Brewing put out a short note announcing that, after a 35-year run, they were winding down all operations. It was a strangely subdued note given the brewery’s historical significance. One of the founding quartet of Portland breweries that started putting out beer between late 1984 and 1986, it played a substantial role in laying the foundation that would place beer at the center of the city’s identity by the early 1990s.

Founders Fred Bowman, Art Larrance, and Jim Goodwin collaborated with Bert Grant early on, building a reputation for quality at a time when little breweries often made bad beer. Portland Brewing would go on to release MacTarnahan’s Amber Ale, one of critical early flagships that, along with Widmer Hefeweizen, BridgePort Blue Heron, and Deschutes Black Butte Porter, helped build an industry. One of the most accomplished beers made in Oregon, it has been awarded a truckload of honors, including six GABF medals, the most recent, a silver, coming in 2018.

Yet it has also been a troubled brewery for most of the past quarter-century, struggling with structural problems, risky decisions that didn’t pay off, and a series of owners disconnected from the city it was named for.

Whenever a major, important brewery like Portland shuts its doors for the last time, we search for meaning in the closure, hoping to find larger lessons. That’s usually the wrong lens to use, however, since the circumstances of every brewery are in key ways unique, and that’s especially true in this case. Speaking with folks since the announcement, a consistent picture emerges of how the brewery got here, and why each person I spoke to led with the same sentiment: the closure was a bit of a shock, but it was definitely not a surprise. Portland was an important pioneering West Coast brewery, but its demise says more about its own particular circumstances than the state of the brewing industry in 2021.

Background

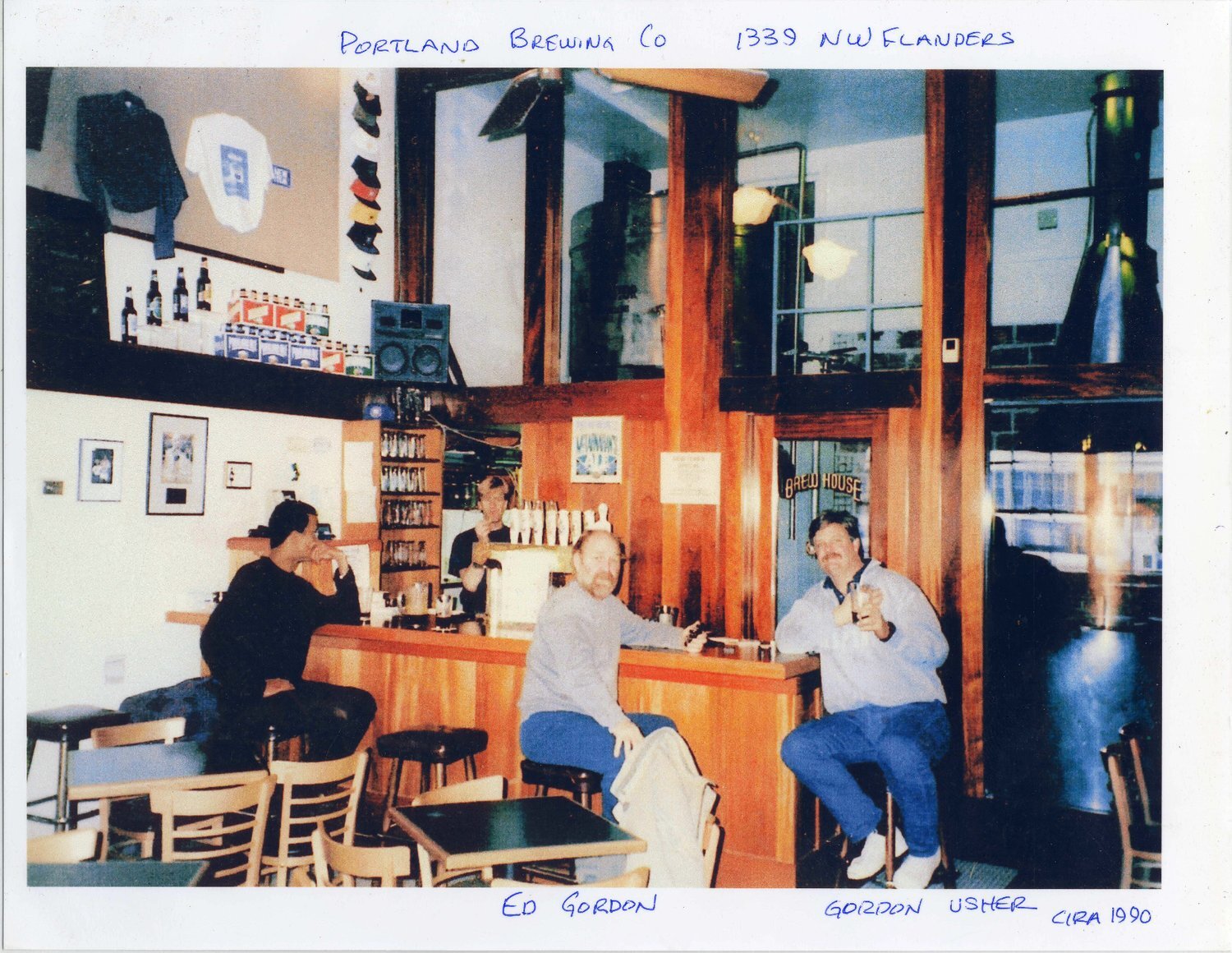

Founded in what is now the Pearl District but was then an enclave of silent warehouses disturbed only by rumbling delivery trucks or freight trains, Portland Brewing was a classic bootstraps start-up. There wasn’t much money for anything, even after finding dozens of small-money investors, which is why the founders located it in that district, just a stone’s throw from Widmer, BridgePort, and the huge Blitz-Weinhard brewery. It was an inexpensive industrial space. (The original location later became the Rogue Brewery pub on NW Flanders—which itself closed last year due to the Covid pandemic.)

The brewery was fortunate that Washington’s Bert Grant wanted to brew beer locally for the Portland market, and even before they opened, Bowman and company had contracted to brew his beer on their new system. It was fortunate not just because it gave them an important revenue stream, but because Grant was a professional, with decades of brewing experience and made sure the brewery was up to standard. Portland has never been the most flamboyant brewery in the city, but even from the start, no one ever accused them of sending out faulty beer.

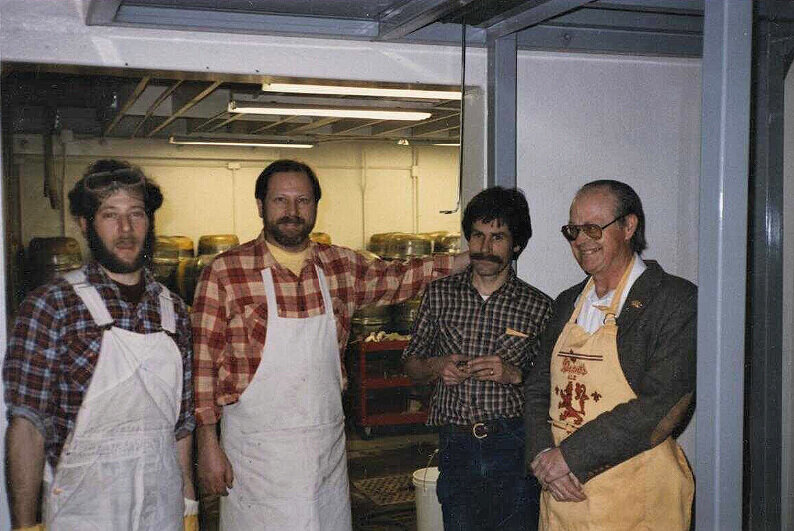

Fred Bowman doing a gravity reading.

The early history of Portland and Portland Brewing are well-told in Pete Dunlop’s Portland Beer, and I encourage you to buy a copy if you want a deeper study. There were a few important developments that paved the road to the current situation, however. In the 1990s, the brewery invested in a beautiful new brewery in a different industrial tract, this one on NW 31st. The mid-1990s craft beer plateau arrived around the same time, saddling the brewery with debt it couldn’t service. “Mac” MacTarnahan, an early investor in the company and the namesake of the flagship, bought the brewery in 1998. That helped Portland find its footing, and for a time things looked good—until MacTarnahan, at the end of his life, sold Portland Brewing to Seattle’s Pyramid in 2004. (Fun fact: the price was $4.2 million, which looks pretty good by the standards of a decade later.)

Pyramid, the ostensible buyer, had its own trouble and soon fell on hard times. Once one of the largest craft breweries in the US, the company began closing down its own breweries, shifting all production to Portland. Eventually, the company did open a small brewery in Seattle near the Mariners’ ballpark, but the bottled beers were still made in Portland. Perversely, despite the brewery’s Portland location, the biggest sellers were all Pyramid products, fueled by Outburst, their double IPA. It was a strange situation: a two-headed brewery located in Portland but dependent on the Washington brand.

The merger of Portland and Pyramid didn’t strengthen the company. To the contrary, it eventually led to a series of acquisitions by increasingly larger and more remote entities, culminating in 2012, when Costa Rica-based Florida Ice and Farm Company (FIFCO, pronounced feef-co) acquired the hodgepodge of breweries which by that time included Magic Hat, Genesee, and US Lebatt’s. FIFCO is a Rochester-based company focused on mainstream beer brands, currently led by its Seagram’s Escapes line of FMBs. FIFCO will continue to make three Pyramid beers in Rochester, but Portland’s brand will be done when the brewery closes in early February. If you want some MacTarnahan’s, now is the time to grab it.

What Led to This?

As long ago as 2013 I called Portland a “zombie brewery,” describing it as a company more interested in looking back than forward (a fact one employee pointed out when we talked this week). Yet when I spoke with folks at the brewery, the story I heard about the last days wasn’t the one I expected. It’s true that Portland Brewing suffered as a result of its remote ownership; FIFCO was a company that while committed to Portland/Pyramid’s success was distant enough it didn’t understand the market or how to appeal to it. Yet that was just one difficulty in a series of problems, the roots of which date back decades. The situation was a lot more complex and intractable, and if anything, FIFCO should be commended for sticking with it as long as they did.

I learned quite a bit by talking with several employees, and I let them speak freely, off the record. FIFCO has been a fine employer: they were given good salaries and benefits, and the company is offering generous severance payments and treating folks with respect. No one wanted to give a formal interview, but our conversations were invaluable in helping me understand the circumstances that led to this end.

Flagging Sales

The nut of any business story is sales, and for Portland and Pyramid, things had been going downhill for years. This is entirely in line with the troubles other legacy breweries have had. Flagships took a huge hit in the mid-2010s, and many breweries never recovered. The Covid pandemic wasn’t the reason FIFCO shut Portland down, but that didn’t help matters. Volume has been in decline for a number of years, and nothing the brewery tried reversed the trend. The past year was especially bad, and nothing suggested there was a path back to increased sales.

No one I spoke to had exact numbers, but the following trend line, which captures only the beer sold in Oregon, illustrates the problem. (Full sales of all products are perhaps three times as large.)

The Facilities

Beyond sales, however, there were other problems. Anticipating big growth in the 1990s, Portland shifted from a brewpub to production model, buying a gorgeous (and expensive) 130-barrel copper-clad German brewhouse. That’s a lot of scale, which is great if you need 40,000 bottles of beer with every batch. But as the market shifted toward experimentation, it became a volume albatross. In recent years brewers did put a two-barrel test system online to populate taps at the brewpub, but they had no way to put small batches into the broader marketplace. It was 130 barrels of beer at a whack or nothing. They also long ago invested in bottles, and changing out their line with cans would have been an expensive upgrade. The brewery was built with 20th-century market conditions in mind, which positioned them badly two decades into the 21st century.

The location was terrible, too. The owners chose to situate the production brewery in another industrial zone, but one far more remote and cut-off than the original location had been. People stopped in for lunch—sans beer—and some popped in for a pint after work, but by seven it was dead. Portland tried to make it a destination gastropub, with formal dining and spendy entrees, and that worked for a time. But with six dozen breweries in town, fewer and fewer people visited. The restaurant closed in 2018.

Finally, FIFCO doesn’t own the brewery building, and the leases were up this summer. (There are actually two buildings on the site, and there may be two landlords—my sources were a bit fuzzy on that.) This, more than anything else, may be the reason the closure happened now.

We all know the difficulty legacy breweries are in. Perhaps if they had stayed an independent duo, Portland-Pyramid would have found a way to revive things. Folks I spoke to mentioned ideas like opening a separate taproom, adding a smaller brewery, and pursuing more adventuresome beers. That’s exactly what the company did in Seattle. The site had apparently done what they’d hoped—revive interest in the brand, infuse the company with money, and give it a physical presence. Alas, Covid, in destroying professional sports crowds, also dealt the Pyramid facility a death blow.

I can also imagine that managers in New York, looking at the 2021 budget, must have wondered what they were doing with this weird little brewery on the other side of the continent. Logistically and financially, it doesn’t make much sense.

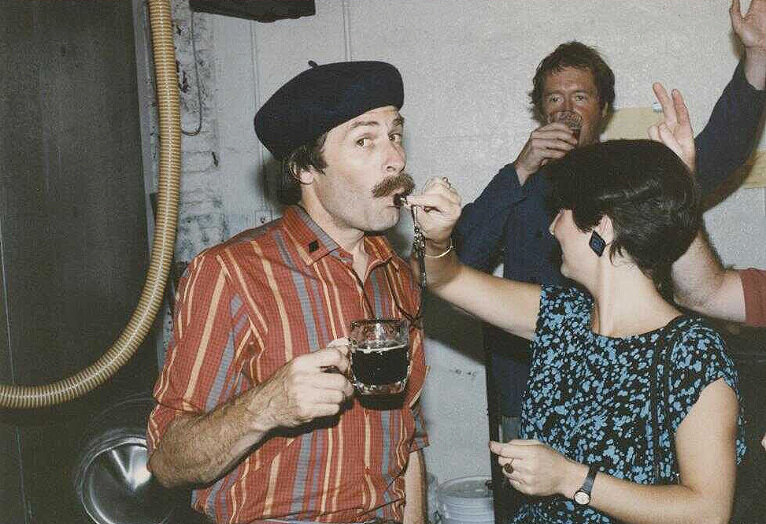

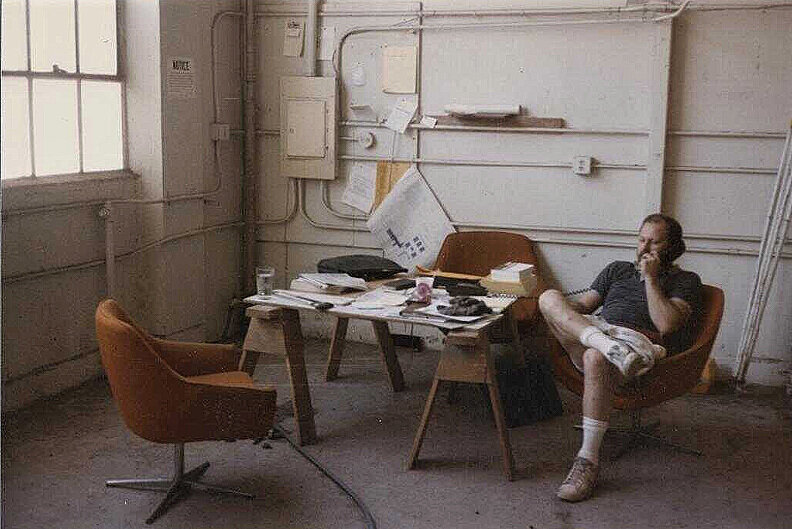

Art Larrance in the makeshift office. This is an amazing photo!

Changing Market

More ominously, FIFCO is moving away from craft beer. Last summer, the company shut down the Magic Hat brewery, and with this closure it will have streamlined production, eliminating small, inefficient satellite breweries. They will continue to support a small range of beers in those lines as long as they sell, and then they’ll let them go, too. And why not? The company now has a single plant, the one at the Genesee Brewery in Rochester. It will make a lot of Genny Cream and focus on the Seagram’s FMBs, which are simple to make and sell. That’s the direction the market is headed anyway, and it is so much easier to make large volumes of simple liquid.

Contrast that with the increasingly baroque world of craft brewing. The most successful companies are the small ones, able to make a huge variety of products and sell them close to home. The products are expensive and lack mass appeal. Beer Twitter spends a lot of time thinking about dry-hop techniques, but from a production standpoint, complex IPAs are a huge amount of work that can’t easily be scaled up. The products are lucrative on a per-unit basis, but there’s no reason to believe they will ever account for a tremendous volume, and anyway, it’s extremely difficult to compete for the few sales there are in that segment. No matter how good a hazy IPA Portland Brewing made, it was never going to win customers from Great Notion’s fan base.

Final Thoughts

The closure of Portland Brewing is significant because it ends a chapter of the city’s brewing history. Three of the first five craft breweries are gone (Cartwright, BridgePort, and now Portland), one has been sold to Anheuser-Busch and may be gone soon (Widmer), and the original city brewery that did so much to prepare the ground for craft brewing, Blitz-Weinhard, closed in 1999. Of the founders, only the McMenamins chain of brewpubs still survives. Collectively, they formed a group that never fully made the transition out of that early phase and continued to be known for old-school beer right to the end.

Portland Brewing spent decades trying to create a follow-up to MacTarnahan’s, but never found it. Had they managed to survive, scaling down, retrenching, and slowly rebuilding, we might have, in another generation, come to think of MacTarnahan’s the way Europeans think of decades-old world classics. What was for years a liability might have become a cherished part of our heritage—a London Pride in Portland. Could the brewery have survived? We could stack what-ifs on top on one another: what if Portland Brewing had chosen the inner East Side for their second brewery? What if Mac hadn’t sold to Pyramid? What if they had opened a second brewpub, with a smaller brewhouse, fifteen years ago? Instead, the decisions they did make have led to this point.

Let’s not go out on a sour note, however. Portland Brewing was by any measure a success. One of the folks I spoke to told me, “We made good beer. People have been buying and drinking our beer for decades.” Yes they have, and that’s one hell of a legacy. That Portland also created one of the iconic beers in Northwest brewing history speaks for itself. I think if you’d asked Fred and Art back in ‘86 how they’d feel to know this is how it turned out, they would have been staggered. Very, very few breweries ever see the success Portland did.

So mourn the loss of Portland Brewing, but be sure to celebrate it as well. Here’s to everyone who made it happen. Congratulations on a great brewery!