Visiting Boston's Big Brewery

I like big breweries and I cannot lie. Big tanks, big pipes, big packaging floors. Little breweries have their own delights, but there's something about the scale, the thump and clang of large breweries, that I can't resist. Last week, while in Boston to give a speech, I carved out time to visit the old city brewery down on the harborside where, as founder Dan Kenary joked, "Whitey Bulger used to dump bodies." Now the 27th largest brewery in the country, it has been at that location for thirty-one years. And by city brewery I mean, of course, Harpoon--not that other one that has "Boston" in the title but which has never been brewed in Red Sox nation.

Although a lot has changed since the body-dumping days, the location is still by no means a glamorous one: it's the working harbor. The warehouse Harpoon found back in 1986 was originally used in the 1930s to build destroyers for the British navy--until December 1941, after which the ships went to the United States. There are still a couple heavy beams running parallel to the canning and kegging lines that have rails on top of them that were used by the shipbuilders. The city owns the land, but they are happy to have a working plant like Harpoon there; in 2008 they signed a lease with the brewery to keep Harpoon there through 2058. When I visited, I started by chatting with Dan Kenary (who's also CEO)--look for the audio to appear on a future podcast--and then joined Jaime Schier, a brewer whose current title is Director of Quality, for a tour.

Harpoon has an interesting reputation right now. For most of the craft era, Boston was an also-ran in beer. Sam Adams had its HQ there, but made an oddly out-of-step amber lager that was not to New England's burgeoning ale-oriented tastes. That left Harpoon with the run of the city until recently, when a whole raft of smaller breweries have come along to spark a beer geek renaissance there (Trillium and Tree House, in nearby Charlton, are both on short lists of the hottest breweries in the country). The absence of much competition allowed Harpoon to become one of the country's most successful breweries, and Harpoon IPA is ubiquitous throughout the city. But it has also meant Harpoon is strongly identified with its flagship and has a staid, traditional quality about it--something like a cask ale brewery amid the hip startups in London. I was interested to see the brewery, hear how what course they have charted for the future, and see some of those big tanks.

The original brewery was a 20 barrel kit, and Harpoon managed to sell an impressive 1,500 barrels its first year. Since none of the founders knew how to brew beer, they hired a recent UC-Davis graduate named Russ Heissner, and brought him to make a beer inspired by English mild ale. (It was called Harpoon Ale, which isn't as boring as it sounds; the brewery's actual name is the Massachusetts Bay Brewing Company--like BridgePort and Pyramid, the name we know it by came from early beers.) They never planned to grow very fast, and indeed have never grown faster than 11% a year.

Kenary continued to work for a bank for years after the brewery was founded, and despite decent sales, it still wasn't profitable. The change in fortunes came when they introduced IPA in 1993. The original recipe was designed by Tod Mott, a legendary New England brewer who would go on to Portsmouth Brewing and make Kate the Great Imperial Stout, finally founding his own brewery in Kittery, Maine. But in the early 90s, he was getting his start as a brewer and was trying to figure out the grist for the brewery's IPA. Harpoon's early beers looked toward London, and the IPA he create bears those hallmarks. Mott was trying to produce a warm, biscuity flavor, but couldn't find the malts to do it. As a desperate measure, he started sending regular pale malt home with twenty employees, telling them to toast it in their ovens. (The results, as Jaime Schier relayed the story, were mixed.) There was a diner across the street from the brewery, and Mott struck a deal with them to toast the malt in their oven during off-hours. Thus was IPA finally born. (The brewery uses Victory malt now.)

The kind of place you might find someone drinking Harpoon IPA.

The success of IPA led to the current brewery, which Schier led Sally and me through. Purchased from Huppmann in 2001, it was a state-of-the art system for its time and has not a kettle but a "dynamic low pressure boiling" system. (If you want to go deep into the weeds, here's a technical paper for more.) The idea is to reduce pressure so the wort boils at 216 degrees, shortening the boil time and reducing boil-off loss. None of this is all that important--most large breweries have advanced tech--but I bring it up entirely as a pretext to tell the following story. The system is very finicky, and at first if the brewers did anything wrong, "wort would go rocketing up the stack," Schier told us. "Cars outside would be glazed in wort." This was probably especially nice in those icy winters Boston gets. Of course, they eventually figured it out and the glazing stories are the stuff of now-amusing memory.

Last year Harpoon made about 200,000 barrels, three-quarters of that on site in Boston (they have a second brewery in Windsor, VT). That's a lot of beer. Ninkasi makes about 100,000 barrels, and they have a large, luxurious brewery and campus in Eugene. The old shipbuilding site is nowhere near as big, and Harpoon's equipment is all compressed into a tight little space. In the pictures in the slideshow, you'll see that the rows of 120-barrel fermenters run up right next to the brewhouse. The cellar and brewhouse are on the same level and literally separated by a few feet.

There's a ten-barrel test brewery on site, too, and it's positioned immediately next to the main brewhouse, almost like a sidecar. Six brewers manage the whole system, which operates around the clock. Every week, one of those brewers gets to work on the little system doing R&D batches that appear on the Beer Hall's taplist. As is my way, I peppered Schier with questions about the system and the beers they make. I asked about how well the German-designed whirlpool handles hops (not well; the German who installed it was appalled that they would sully it with hops in the first place), which mash rests are used on IPA (one, at about 153°) and whether they have experimented with kettle souring (yes, but tart beers aren't really in their wheelhouse).

The cool thing about actually walking the brewery floor and asking these questions is that a picture begins to emerge. Every brewery is different. It's not just the layout or even the beers the brewery makes; in every brewery the brewers think about beer differently. During my interview with Kenary, I suggested Harpoon had a British lineage, but he rejected that, pointing out how many non-British beers they make. He kind of understood why I would say that, but it wasn't really right. Later, when we were standing by the test brewery, I was asking about New England IPAs (yes, one's on the way, but probably won't arrive until 2018), barrel-aging (they have a small program), and other beer geek favorites. The next thing Schier said seemed to crystallize everything I'd been absorbing about the brewery and served as a once-sentence mission statement. Yes, he said, they do experiment with all kinds of beers, but ultimately, they don't make beers with esoteric flavors.

“If you don’t want a second pint, that’s not a beer we’re likely to make.”

That's exactly right. Harpoon's DNA isn't English, it's the pub. They make beers to be drunk in twos and threes, often on draft. I was absolutely gobsmacked when we were standing in front of the canning line and Schier said, "just under half our beer goes out in draft." For a brewery of that size, that's an enormous amount of draft beer. (It's also almost identical to the percentage of beer consumed on draft in the UK, but let's not get bogged down in minutiae.) The reason is because Harpoon is the kind of beer you want when you're watching a Red Sox game or a Patriots game or a Celtics game or a Bruins game (or, although I can't imagine this happens much in Boston, doing something other than watching a game).

After our tour, we repaired to the Beer Hall for a pint. They had a pilsner, so naturally I had a sample of that first. Jaime was pretty excited about an oatmeal pale ale they had on, though, so I grabbed a pint of that. (Observation: when the brewer is willing to tell you he's excited about one of his beers, drink it.) It was a case in point for the Harpoon Way. After my first sip, I thought, "not bad." It was a lightly hoppy, light-bodied but creamy pale ale. We started chatting about bicycling, I think. One of Jaime's non-beer passions is cycling, and he'd just completed a 300-mile, multi-state tour for charity. At about the halfway mark, I noticed the beer was drinking really nice and upgraded it in my mind--definitely a nice beer. We kept talking until it was time to say our goodbyes, and I finished the beer. The hops seemed to be opening up, and I was impressed by how a sweet, biscuity mid-palate note led to a very dry, crisp finish. At that point, I was really impressed; rare is the beer that keeps on improving the more you drink it. I was ready for my second pint.

________________

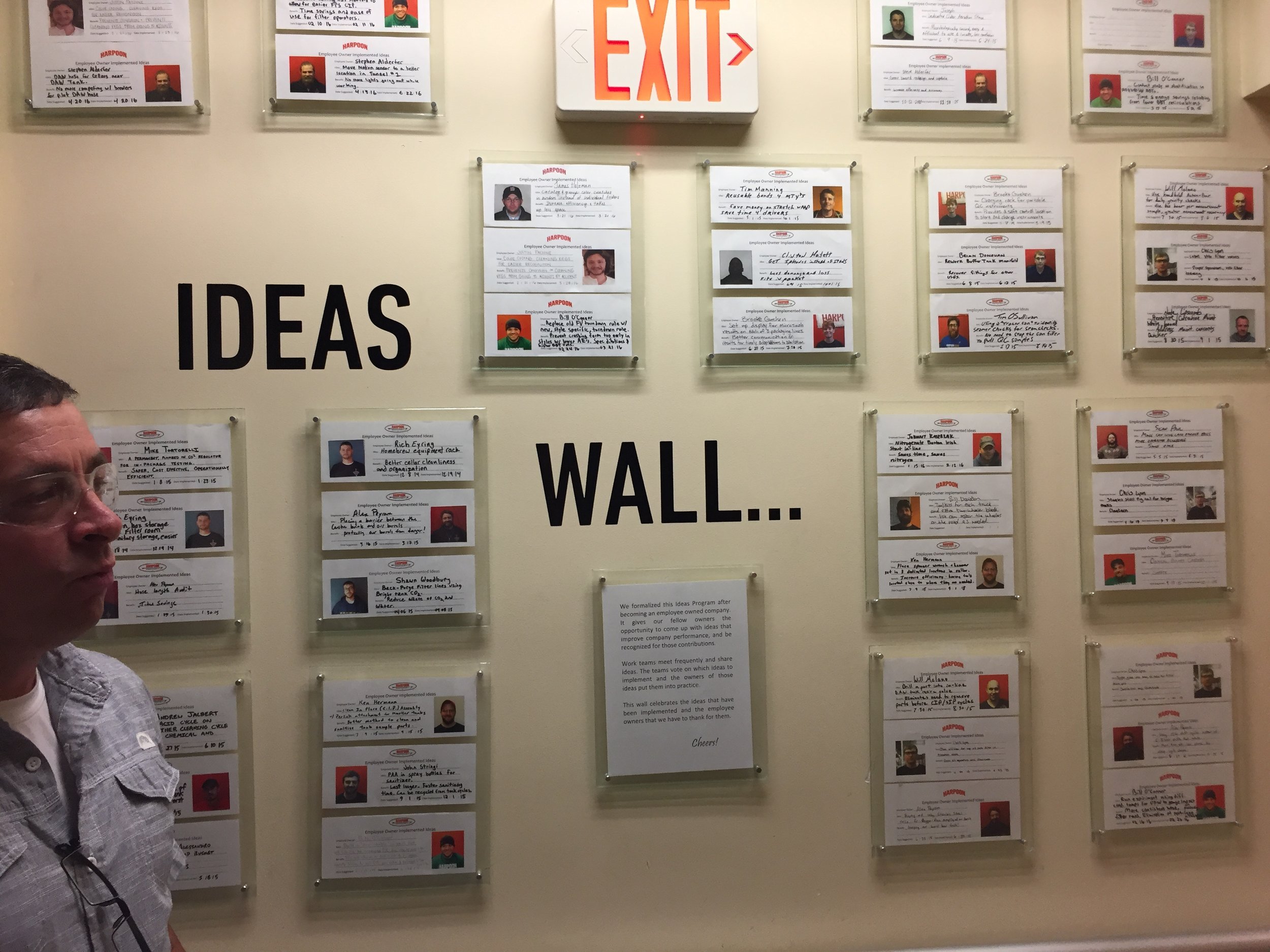

A few years ago, Harpoon set up an Employee Stock Option Program (ESOP) and co-founder and co-pillar of the brewery Rich Doyle left. When he retires, Kenary plans to sell his stake into the ESOP. Harpoon is the oldest brewery in Massachusetts, and like many legacy breweries, production has stalled amid the growth of smaller, newer entrants. It's really not in the brewery's DNA to start churning out dozens of experimental new offerings a year. But Boston, despite its very blue politics, is a conservative, traditional city in many ways. It cherishes its heritage, so being a "legacy" in Boston is not a bad thing. Churn and change is the way of markets, but there are no signs Harpoon plans to abandon its identity anytime soon. The brewery self-distributes its beer in Boston, and is preparing to weather a period of stalled growth.

The course charted for the brewery, then, is: steady as she goes. Kenary and company are betting that their beer and their brand are going to continue to wear well in the city. Kenary has no plans to go national, and Schier mentioned that even some markets, like Ohio, might be too far away for Harpoon to be relevant. At maximum capacity, they might be able to squeeze 250,000 barrels out of their current site, but not more. In their wildest dreams, they will be a slightly larger regional brewery identified with the city of Boston. They have 41 years left on a fifty-year lease, and they're betting that the long term trends in beer look pretty good for well-made, sessionable beers.