Hops Are Finding Equilibrium

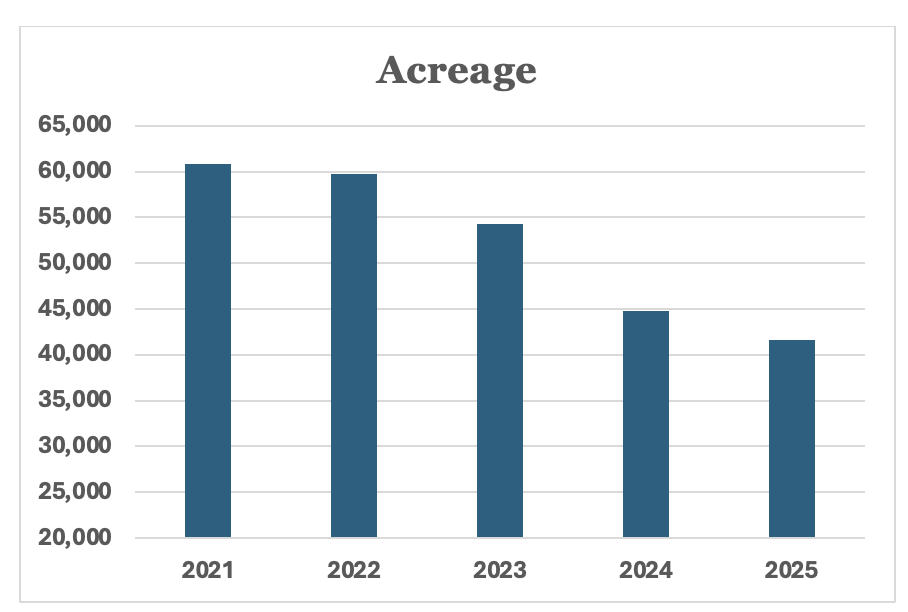

The USDA released its annual National Hops Report a couple weeks ago, and it suggests that things may becoming back into equilibrium. Once again, hop acreage and total crop grown (in pounds) were down again this year, by 7% and 5% respectively. That is actually not a terrible decline, however—and indeed, the value of the crop was (barely) in the black. Consider how much the hops have declined by these three metrics over the past five years:

Acreage, -31.6% (60,872 to 41,654 acres)

Total production, -28.1% (115.6 million pounds to 83.1 million)

Value, -32.4% ($661.6 million to $447.5 million)

The best news, reported in September, is that the massive hop surplus is finally coming down, falling from 136 million pounds to 116 million pounds (-15%). Interestingly, that surplus includes amounts held by breweries—which may be more than they need but is more like stock. Growers and dealers have a surplus of 95 million pounds. In the late teens, hop acreage was growing to meet anticipated growth among breweries, but that didn’t happen. Growers optimistically kept acreage up, and this created a huge backlog in warehouses. Starting in 2023, growers really cut back their acreage, and now that is finally allowing the surplus to work its way out to brewers.

For the visually-oriented, here are some five-year graphs of these metrics. Note that the graphs do not extend down to zeros—I shortened them to enhance the declines.

If you’d like fuller explanations on these numbers and more, both Stan Hieronymus and Eric Sannerud have great reports that go at them somewhat differently. Needless to say, you should be subscribing to both of their newsletters if you’re interested in hops. I will quote from each of them where I think they have especially interesting info:

Stan: “Hop production Germany was higher than forecast in August, but still down 7.2% to 43,141 metric tons…. [O]nly 10 varieties account for 92% of volume (Herkules alone is 51%). In the US, 10 varieties account for 72% of production.”

Eric: “When a variety falls below that threshold its acreages get totaled in the ‘other varieties’ category. In 2025 36% of Idaho acreage and 10% of Washington acreage fell into the other category. These are massive increases of ‘other varieties’ from 2024.

Stan: “In the Czech Republic, production increased 6.4% to 6,909 metric tons as a result of higher yields … [and] Saaz still accounts for 75% of production.”

Eric: “Mt. Hood has popped back up on the acreage report [and] may be the biggest winner in the rise of craft lager. Hallertauer: Down to 44 acres from 160 in 2024. Saaz (US): Down to 84 acres from 372 a year ago. Talus: up dramatically from 148 to 492 acres. Strata: Fell down 44% to 326 acres from 574 in last year.”

Stan: “As expected because acreage increased, Citra production grew 15 per cent, to 12.5 million pounds (5,666 metric tons), comparable to Saaz production (5,207 mt) in the Czech Republic. That’s 32 percent less Citra than farmers harvested in 2021.”

Eric: “Total privately controlled acres increased slightly to 65% in 2025. This roughly 65/35 split has been stable since 2022 following the dramatic rise of private acres from ~2014 to 2022. From the 2025 report I mark ~26,000 acres of aroma hops, 7,300 in public, 18,700 in private for a 71/29% private-public split in the aroma market.”

I will leave you with a last comment from me. As we exit the period of craft beer’s novelty era, when breweries made dozens of IPAs every year, it looks like it’s impacting not just the amount of hops brewers are buying, but the diversity. When I talk to brewers about new hop varieties, they are often hazy about them and most are not sampling every new one that comes out. Brewers seem to be more interested in hop products as a way of enhancing their beer. These products focus on the most popular hop varieties, which increases the “stickiness” of the major varieties.

Finally, working with new hops is a time-consuming, expensive project, in which breweries have to figure out how the hops behave, how well they play with other hops, and when to use them in the process. All of that makes experimentation, in a period where breweries are brewing fewer beers a year than they did in the late teens, and early less attractive prospect. I think we’re seeing that in the way the hop market is evolving. This is an interesting development, because there are more hop breeding programs now than ever before.