The Hop That Earned Its Name: Dolcita!

Three years ago, I wrote a long article about the process of breeding a single new variety of hop. The journey starts with thousands of little plants in a greenhouse and—if all goes according to plan—results a decade later in a commercially-viable hop. For that article, I chose to look at one of the hopefuls:

If Michael Ferguson gets his wish, the creamy-sweet hop currently known by the clinical name HBC 1019 will one day be called something more poetic. If it’s a very, very lucky hop, it will join the ranks of named hop varieties that become signature flavors defining the hoppy ales driving American craft brewing. For the moment, however, it’s a mere aspirant, a talented but unproven performer who has yet to show she has what it takes.

The majority of hop varieties, even when they reach the advanced stage 1019 had, don’t make it to that glorious moment of commercial birth commemorated by an official naming ceremony. But I got lucky, and little 1019 was the little lady that could. A couple weeks ago, the collective that bred and nurtured her announced her grand coming out: the experimental name abandoned, her new name is Dolcita.

So who is Dolcita? In this post we’ll get to know her a little better by hearing from John I. Haas breeder Michael Ferguson and Yakima Chief Ranches Vice President of Research Ryan Christian. But first, a few details.

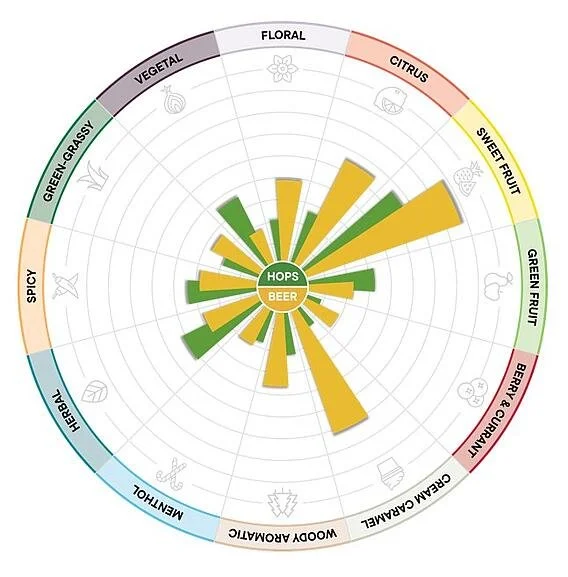

Sensory Description: Stone fruits, (notably ripe peach and creamy), tropical flavors (caramelized pineapple), bright citrus (tangerine and orange), and sweet aromatics evocative of tropical daiquiris and dark rum.

Alpha Acids: 10-12.2%

Beta Acids: 8-10%

Total Oils: 1.3 - 2.2 ml/100g.

Breeder Notes: “Dolcita originates from a 2016 cross between two developmental lines within the HBC program. Agronomically, it’s a high-yielding hop with an early harvest window, strong field performance, and good storage stability. The name… combines the Italian word ‘dolce’ (meaning ‘sweet’) with the Spanish diminutive suffix ‘-ita,’ resulting in a term of endearment often interpreted as ‘little sweetie’ or ‘sweetheart.’

Genuine Excitement

New hop releases are not what they once were. The overall hop market is down, and the beer industry, also in a trough, is far less experimental than it once was. There have also been some misfires along the way, including Sabro, from the same breeding company that produced Dolcita (see note at the end about the three-headed hydra that bred Dolcita). Michael Ferguson acknowledged the apprehension companies must feel after completing such an incredibly complex, lengthy, and expensive project.

“Hops have just been a really humbling crop to enter. I mean, I'm 50 years old and I've been in ag my entire life. I grew up on a grain farm and a livestock farm and then went to the produce business. But man, hops are just—there's a reason why it's just such a volatile market. And it drives me crazy.”

In other words, there are no guarantees in the hop-breeding world. That said, over the past couple years, 1019 was generating positive buzz. I’ve heard brewers mention it, and those who follow hop-breeding started gossiping about how 1019 may be the next named hop. Despite the long odds, both Ferguson and Ryan Christian occasionally let their enthusiasm peek through. Christian momentarily effused: “It’s a very exciting, aromatic hop. We always include examples of what was 1019 in our sensory and brewing trials, and it’s always phenomenally likable. The hedonic ratings, the uniqueness ratings—it’s always at the top of the charts.”

One thing the Hop Breeding Company does well is launch hops, and you have probably saw something about Dolcita’s release. People are genuinely excited—or at least intrigued. Ferguson estimated there a couple hundred acres of Dolcita is in the ground (it will be picked in mere days or weeks), enough to satisfy the demand of any brewery ready to experiment with it.

Sensory and Chemistry

For the past hundred years or more, when breeders went to work on a new hop, their instruments were their senses: they sniffed and tasted the hops, and looked at how they grew in the field. Those are still their principle tools, but Dolcita is one of the first hops to get a serious boost through chemical analysis—and that’s one reason the breeders are excited about the hop.

Dolcita, or 1019, was starting to emerge as one of the potential winners when Christian joined Yakima Chief after getting a PhD from Washington State. “Dolcita was being developed just as these tools were becoming available,” he told me. “One of the things that immediately popped out to us was a moderately-high to high proportion of geraniol.”

Why was this significant? For decades, hop-growers tracked the classic terpenes found in hops: myrcene, humulene, caryophyllene, and so on. But these are extremely volatile compounds; apply any heat and they vaporize and drift right off with the wort’s steam. Christian says there’s a saying around Yakima Chief: “If it ends in -ene, it doesn’t make the scene.” But not all compounds are so volatile.

Geraniol, by contrast, is one of those compounds Yakima Chief has labeled a “survivable” (linalool is another). Less vaporous than terpenes, these will survive more readily through to the finished beer. So a higher proportion of survivables indicates a versatile hop that can be used earlier in the boil or later on the cold side. It wasn’t the only survivable the scientists at YCR observed.

“The other thing that popped out on the GC values [gas chromatography],” he continued, “was a high percentage and a high amount of the soluble esters.” Christian, to his enormous credit, spoke to me almost entirely in language I could understand—until we got to soluble esters. He dipped into molecular structures, and I lost the thread a bit until he came back to the upshot: “For instance, 2-Methylbutyl isobutyrate is one that’s highest in Dolcita. That can have an ethereal fruity quality or an apricot. And that provides that peachy aroma we get in Dolcita.”

The final chemical piece are the thiols, which Christian described as “fairly low.” That may not be terrible. Thiols are associated with intense tropical fruit aromas and flavors, but can also have a savory, catty, or garlicky component. By all reports, Dolcita is naturally low in the thiols that produce the savory stuff (unless growers push the harvest windows too late).

Dolcita may have spent her tender years in this very greenhouse. Photo: Michael Ferguson

Great Agronomics

Brewers and drinkers after don’t consider how a hop grows—but that can be an important element in its success or failure. For whatever reason, aroma hops often produce an anemic yield. Citra, almost the perfect hop in the brewhouse, is a troublemaker in the field. It only produces 1,500 pounds per acre (growers like to see 2,000, and high alpha varieties can generate 3,000). It also comes in later in the harvest, along with a glut of other varieties.

Dolcita is great in the field. It produces 2,000 to 2,100 pounds per acre. Additionally, “it's a relatively early pick and the yield was consistent in all the years we've grown it,” Ferguson said. In Yakima, there aren’t that many early-harvest hops. That matters because hop farms harvest for a month, and hops have very specific harvest window. It’s a lot easier to plan a harvest when you have early, mid-, and late harvest varieties.

Hops sometimes vary in expression year-to-year, but that hasn’t been a problem with Dolcita, either. “The flavor's been absolutely consistent the whole time we’ve had it in—I guess we've had that block in for like five years.” All these elements will make Dolcita a predictable hop that’s easy accommodate on a farm. Even if the early demand is slow, the agronomics could keep Dolcita in the ground.

The Next Citra?

Every time I speak to someone who works in hop breeding, I probe to find out what their expectations are. Citra literally revolutionized brewing in the U.S., as brewers shifted the way they brew to capture all its glorious tropical-citrus flavors. Mosaic was nearly as big. With each new release, however, it seems like the bump got smaller. Brewers have so many choices now, both in terms of type as well as hop products, that it’s hard for a new variety to break through.

No one I’ve spoken to thinks there will ever be another Citra, and Ferguson and Christian doubted it, too. Indeed, because of that surfeit of new hop varieties, failure is as likely as modest success—and modest success is probably the ceiling. Perhaps I should quit using Citra as a benchmark, though. The question isn’t whether a hop will revolutionize brewing and become the country’s best-seller, but whether it can find its audience and make a profit. Outfits like the Hop Breeding Company think the answer is yes, because they continue their robust breeding program. Perhaps we don’t need another Citra

For these reasons Ferguson was circumspect. He was plainly tickled to see his hop make it over the finish line, and I detected a sense of happy exhaustion at the length of the journey. He knows how long the odds are, however, and wouldn’t predict it would be a hit. He would only go as far as vouching for Dolcita’s character, which he admires very much. “We knew instantly it was excellent in beer. It was a unique hop, and that’s a big effort to [breed]. As far as brewers looking for a new tool, I mean, this is it. If you want to make a flavor-differentiated beer, this is the hop that'll do that.”

The rest is up to the brewers.

A final note. Dolcita, like sisters Citra and Mosaic, was bred by the the Hop Breeding Company in 2003. It is in turn a joint venture between John I. Haas and Yakima Chief Ranches, so you will see both YCR and Haas identify it as a proprietary cultivar. Confusing! But that seems to be the nature of hop breeding.