Troubles With Travel

If you were to name the four or five hottest breweries right now, measured in beer geek coolness points, Boston's Trillium Brewing would have to be on that list. They are makers of many different types of beer, but are famous for being one of the charter members of the New England IPA movement, with all the requisite rarity and excitement. Well, despite having failed to find any of their rare offerings when I was back in New England in November, I got to try my first can when friend-of-the-blog Mason Astley spent his hard-earned time and money securing Fort Point Pale Ale and sending one my way.

I was very excited about this because, while I think there's no special style* to be found here, I have been mighty impressed by the work New Englanders have been doing with hops. Places like Maine Beer Co, Bissell Brothers, and Hill Farmstead understand our little friend, Humulus lupulus. Maybe not uniquely (I could point to a few guys around here who have passing familiarity), but decidedly. And by all accounts--including Mason's--Fort Point is one of their best beers. (Not that these things matter too much, but it is a top-ten pale as rated by BeerAdvocates).

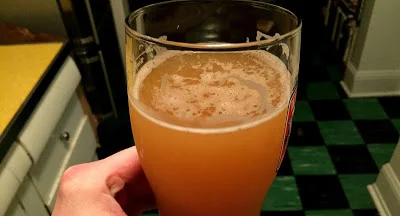

So it was to my surprise and disappointment to discover this waiting for me:

So murky as to be dark pouring out. Very much a pond water rather than Orange Julius cloudy. Poor head, gone in 30 seconds. Aroma is orange passionfruit with a hint of sweat underneath. Flavor is fairly sharp bitterness with a rindlike astringency. Mouthfeel is fluffy to gritty. The tropical notes present far more on the nose than palate. Very little malt character. Slight burnt rubber aftertaste.

Those are not the tasting notes of a world-beater. Those are not even the tasting notes of a particularly good beer. I sent them to Mason last week and he was surprised and chagrined--this was not the beer he knew. There's no accounting for taste and I could just be missing the subtle genius of this beer. I don't think that's what's going on here; I believe were Mason to have tried this beer, he would more or less agree with the notes. So what's going on?

Beer is inherently unstable. Brewers tease chemical compounds into an arrangement that will not last. They begin interacting with each other and that particularly nefarious enemy oxygen will begin to stale the flavors. This happens in all beers, but not at the same rate. Some beers are incredibly fragile, ready to collapse like a house of cards into a pile of decomposing, once-brilliant flavors. Among the most delicate elements are hop flavors and aromas, which are driven by volatile compounds that begin degrading immediately even in the best circumstances. Send a beer across country, where it may be subjected to temperature fluctuation and agitation--two accelerants to degredation--and even a relatively young can might well end up like the one I received.

This is an important cautionary tale about modern IPAs. So much of the hop character comes not from the more stable iso-alpha acids formed during longer boiling, but volatile compounds in the oil. We know how evanescent those flavors and aromas can be from observation, but I don't know how much study has been done on trying to stabilize them in the package. Moreover, we're in a realm of brewing that is out in front of the science. When we were in Corvallis last week, hops researcher Tom Shellhammer mentioned that perceived bitterness and astringency may also come from other sources (polyphenols?--I can't find the passage from our interview) than iso-alpha acids. How do these astringent elements change with time, agitation, and heat? I was picking up sharp, prickly notes that had a quality of astringency, like citrus rind. Was that present in the brewery-fresh version?

The category we now call IPA is hugely broad, and at one side of the spectrum can be made so that it's pretty shelf-stable. But on the other side--the side that tickles the beer geeks' fancy--it's not clear that this is the case. What happens when a brewery like Trillium scales up and has the capacity to start sending their beer around the Northeast? Can they find a way to package the freshness so that it lasts even 30 days? I have my doubts. And interestingly, I kind of hope it's not possible to stabilize this. If breweries have to sell their beer at the source to ensure these flavors and aromas survive, that means people will have to continue to patronize them there. That means I won't be getting any brewery-fresh Trillium in Oregon, but I can live with that if it encourages a market for hundreds of small breweries nationwide serving fresh beer.